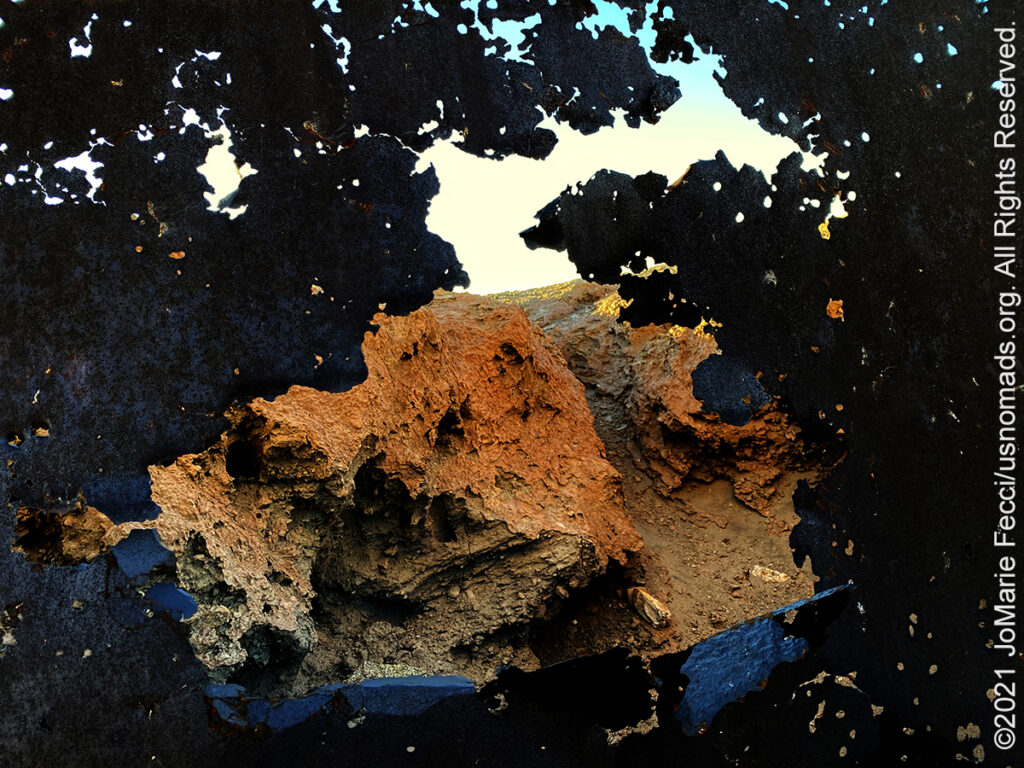

The late afternoon sun scraped across the desert’s surface spotlighting the rusted remains of giant metal tanks full of sand nestled in between the Cargo Muchacho Mountains along the Arizona-California border. I was drawn to this strange specter in a barren patch of scrub. Most of what remains of the Tumco townsite blends in to the landscape, and often times, only traces of the past can be inferred — a rectangular outline of fallen rocks that was once a building or the straight edge of an old road poking out from the sand. Though there are a few intact building ruins, what really stands out on first encounter are those enormous metal cyanide vats, rusted and corroded, falling apart, but still dominating the landscape, a metaphor perhaps, for the way the mine dominated the life of the town.

Tumco, originally known as Hedges, was one of California’s earliest gold mining towns. Gold was first discovered here by Spanish colonists as they moved northward from Sonora, Mexico. According to legend, two young Mexican boys returned bare-chested to their family’s camp one evening carrying their shirts filled with gold ore. These muchachos cargados or “loaded boys” became the namesake for the Cargo Muchacho range. Another version of the story says the boys found the gold while looking for horses or mules that had strayed. In either case, the Cargo Muchacho Mining District was established in 1862 and when the Southern Pacific Railroad completed the Yuma to Los Angeles line of its transcontinental route in 1877, the rails ran within two miles of the Cargo Muchachos and a gold rush began.