100 Days Journey: Part 1 – Heading West

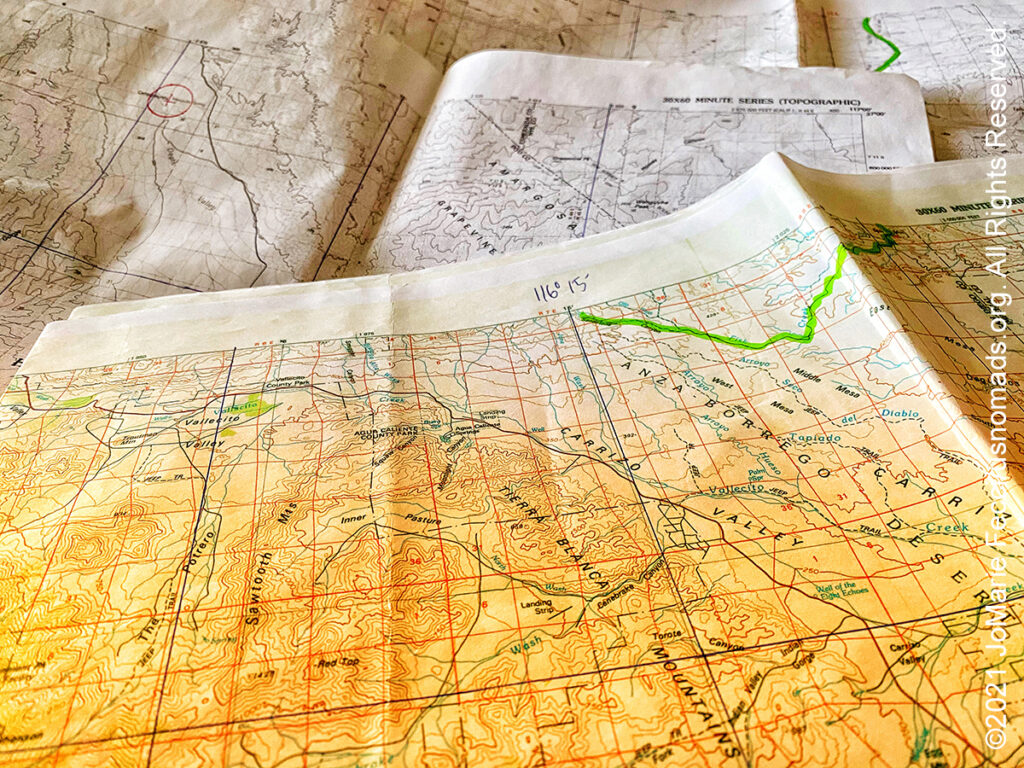

The journey begins on Long Island, New York, with route planning and preparation before a quick sprint westward towards Arizona. My highway route goes west, then southwest through NY, NJ, PA, OH, IN, IL, MO, OK, TX, NM and AZ, where I slow down and start the real wandering. Still, I make plenty of stops along the way to break up the drive with short hikes and interesting photo ops, as I work my way to one of my favorite places in the southwest — the Imperial Sand Dunes. (Click through the images below for each day’s notes)…

Note this map provides an overview of the first segment of the journey headed west. The route on this map shows the overall direction of travel and key “stops” but does not include any detailed GPX tracks for backcountry trails, etc…

The Army Heritage Trail is located on the grounds of the US Army War College in Carslile, PA. The trail is an outdoor museum that complements the indoor exhibits of the Heritage and Education Center, and highlights nearly every era of Army history with different exhibits and large artifacts. Designed to provide an immersion experience that allows the visitor to walk into each period represented, the Trail also serves as a stage for living history presentations by historians serving as interpreters. Fourteen individual exhibits include full scale reconstructions of a French and Indian War way station, Redoubt Number 10 from the Revolutionary War siege of Yorktown, a section of the Antietam battlefield, a Civil War winter encampment with cabins, a WWI trench system, a WWII company area, a replicated Normandy Bocage scene from World War II, a Current Operations HESCO Bastion barrier checkpoint, and an interpretation of the Vietnam helicopter air assault at Ia Drang that includes a period Fire Support Base. Additionally, there are numerous smaller exhibits featuring armor, aircraft, and artillery from several different eras of U.S. Army history. The Army Heritage Trail is open for visitation dawn to dusk daily.

The Route 66 State Park, close to metro St. Louis, Missouri, has displays showcasing the historic route and the visitor center is in a 1935 roadhouse that sat on the original Mother Road. But one of the most interesting aspects of this park is that it is located on the site of a former environmental disaster. The town known as Times Beach was once home to more than two thousand people along the banks of the Meramec River. During the 1970s oil made from chemical waste was repeatedly used to control dust on area roads. After a series of unexplained deaths and illnesses the CDC investigated and determined that dioxin was present in the soil. The EPA was brought in and the entire town was condemned in 1982 after the level of dioxin—contamination was revealed. It was the largest civilian exposure to the compound in the history of the United States. Residents were permanently evacuated in a federal government buy-out of the entire town. Although the decision for relocation in 1982 was made in the best interests and safety of the Times Beach residents, the evacuation was not an easy transition. Eight hundred families had to leave their lives completely behind. The toxic site cleanup was completed by 1997 at a cost of close to $200 million, and the restored land was turned over to the State of Missouri which created the 419-acre park commemorating Route 66 in 1999.

The Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge was established to protect species that were in grave danger of extinction, and to restore species that had been eliminated from the area. The 59,020 acre refuge hosts a rare piece of the past – a remnant mixed grass prairie, an island where the natural grasslands escaped destruction because the rocks underfoot defeated the plow. The refuge provides habitat for large native grazing animals such as American bison, Rocky Mountain elk, and white-tailed deer. Texas longhorn cattle also share the refuge rangelands as a cultural and historical legacy species.The efforts to perpetuate the major species of wildlife once imperiled have been very successful. The big game herds have increased to the point that they are no longer are in danger. The reintroduction of some species ensures wildlife once native to the Wichita Mountains will always remain on the landscape. Recent reintroductions include the river otter, burrowing owls and the prairie dog, which is now flourishing in four areas of the refuge.

Cadillac Ranch is a public art installation and sculpture created in 1974 by Chip Lord, Hudson Marquez and Doug Michels, in Amarillo, Texas. The project was funded by an eccentric millionaire, Stanley Marsh 3, who also owned the land that became the site of the “ranch.” The installation consists of ten Cadillacs, from between 1949 and 1963, buried nose-first in the ground. Installed in 1974, the cars were either older running, used or junk cars — together spanning the successive generations of the car line — and the defining evolution of their tailfins. Cadillac Ranch is visible from the highway, and though located on private land, visiting and spray-painting graffiti is encouraged.

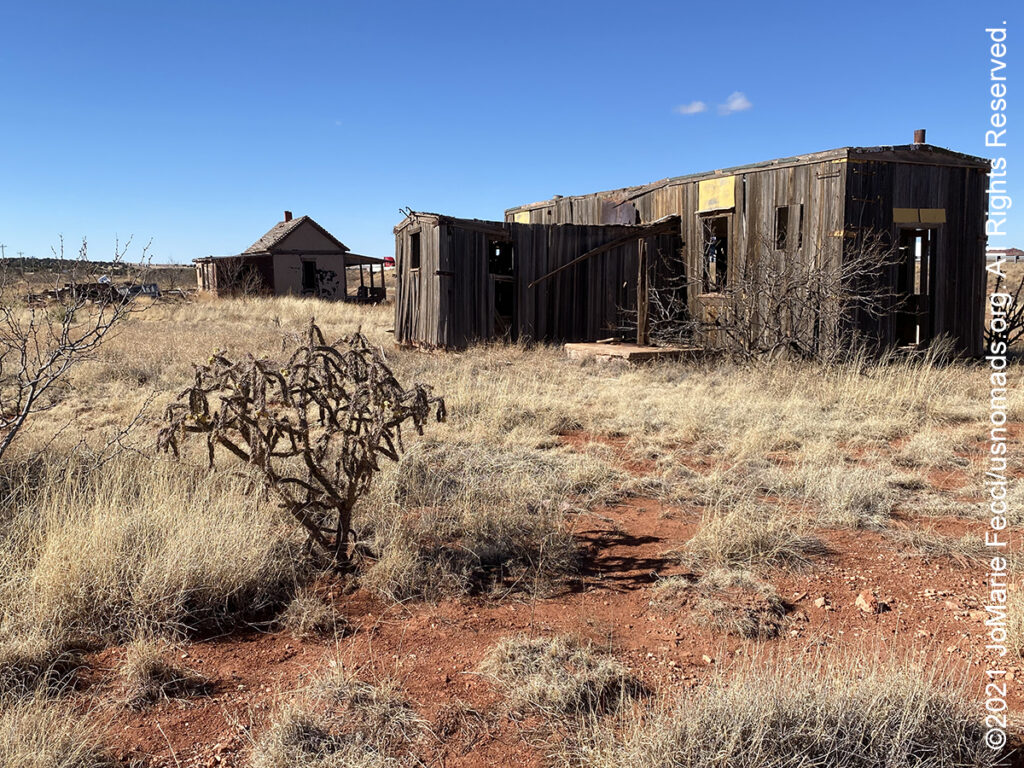

Cuervo, New Mexico, is located along Interstate 40 a little more than 15 miles east-northeast of Santa Rosa. It consists of four streets south of I-40 and two streets north of the interstate, and nearly all of the buildings in the community are abandoned and very deteriorated. The town began in 1901 when the railroad came through and continued to grow as the surrounding land was opened to cattle ranching in 1910. Then Route 66 came, and the town’s population peaked in the 1940s at over 300. When the Interstate replaced Route 66, parts of Cuervo were literally buried and the town was physically split in half. The superhighway allowed travelers to bypass the town and residents slowly abandoned it. The community is virtually a ghost town now, with only two homes that appear updated and inhabited, along with one auto repair business.

El Malpais National Monument, located near Grants, New Mexico, is an extremely barren and dramatic volcanic field covered in old lava flows, sandstone bluffs, ice caves, and lava tubes. The early Spanish explorers named this area El Malpais, meaning “the bad country” or “badlands” because they found the jagged and jumbled black rock treacherous to navigate. But people have adapted to and used this diverse and mysterious landscape for a myriad of purposes for more than 10,000 years. For thousands of years American Indians have found ways in which to live in, around, and sometimes on these “bad lands.” Human occupation was the greatest between 950 A.D. and 1350 A.D. when Ancestral Puebloans built the first permanent structures in the area. Today this richly diverse volcanic landscape offers solitude, recreation, and adventure.

The Painted Desert is a landscape of badlands that run from near the east end of Grand Canyon National Park and southeast into Petrified Forest National Park. It is most easily accessed from within the Petrified Forest National Park. The Painted Desert is known for its brilliant and varied colors. It was named by an expedition under Francisco Vázquez de Coronado on his 1540 quest to find the Seven Cities of Cibola, which he located some 40 miles east of Petrified Forest National Park. Finding the cities were not made of gold, Coronado sent an expedition to find the Colorado River to resupply him. Passing through the wonderland of colors, they named the area El Desierto Pintado or “The Painted Desert”. The multicolored landscape is composed of stratified layers of easily erodible siltstone, mudstone, and shale of the Triassic Chinle Formation. These fine grained rock layers contain abundant iron and manganese compounds which provide the pigments for the various colors of the region. Thin resistant lacustrine limestone layers and volcanic flows cap the mesas. The erosion of these layers has resulted in the formation of the badlands topography of the region. Much of the Painted Desert within Petrified Forest National Park is protected as a National Wilderness Area, where motorized travel is limited, but it continues north into the Navajo Nation, where off-road travel is allowed by permit.

Bulldog Canyon, located in the Mesa Ranger District of the Tonto National Forest, is 34,000 acres and provides approximately 20 miles of open routes for motorized recreation. It is a popular dispersed camping destination for off-roading. Bulldog Canyon routes are all full-size vehicle width and provide access to the beautiful Sonoran desert and Goldfield Mountains. There are six access points: Blue Point, Usery, Wolverine, Hackamore, Dutchman and Willow. A Tonto Motorized Vehicle Use Permit is currently required for this area, available at Recreation.gov. Please remember to stay on the routes. Driving off-road is prohibited on the Tonto National Forest. Permits are not available at the District Office.

The Kofa National Wildlife Refuge is located in Arizona northeast of Yuma and southeast of Quartzsite. The refuge, established in 1939 to protect desert bighorn sheep, encompasses over 665,400 acres of the Sonoran Desert. More than 80 percent of the refuge is designated as wilderness. The name Kofa is a contraction of the name of the King of Arizona gold mine, which was active from 1897 to 1910. The refuge is dominated by two mountain ranges, the Castle Dome and Kofa Mountains, which rise abruptly from the plains of the Sonoran Desert. Although these mountains are not especially high (the tallest peak is less than 5,000 feet), they are extremely rugged and provide excellent habitat for plant and animal species adapted to the harsh desert climate. Towering saguaro cacti reach up to 50 feet in height and are perhaps the most distinctive cacti found on the refuge. Able to store large quantities of water in their leaves, stems or roots, cacti thrive in the desert climate. Closer to the ground, prickly pear, cholla, hedgehog, pincushion, and barrel cacti, as well as desert night-blooming cereus, thrive. The vast desert environment is host or home to numerous mammal species, the majority of which are nocturnal and forage at night while the temperatures is cooler. Motorized vehicle traffic is limited to designated roads identified by numbered markers at junctions and vehicles may pull off and park only up to 100 feet from designated roads. Speed is limited to 25 MPH, or less as posted. Campers may select their own campsites. However, camping within 1/4 mile of water is prohibited by State law.

Tumco is an abandoned gold mining town and is also one of the earliest gold mining areas in California. It has a history spanning some 300 years, with several periods of boom and bust. Originally named Hedges, the town was completely abandoned in 1905, victim to speculative over-expansion and increasing debt. Renamed Tumco in 1910 — after The United Mines Company — another attempt to go after the gold proved just as costly. By 1911, the diminishing prospects of the mines forced the miners and their families to return to Yuma, signaling the end of Hedges/Tumco as a community. Gold was first discovered by Spanish colonists as they moved northward from Sonora, Mexico. According to legend, two young boys came into their camp one evening with their shirts filled with gold ore. These muchachos cargados (loaded boys) were the namesake for the Cargo Muchacho Mountains, where the Tumco deposits occur. Following the first discovery of gold, numerous small mines were operated by Mexican settlers for many years. In 1877, the Southern Pacific Railroad completed the Yuma to Los Angeles line of its transcontinental route. With the presence of the mountains, a gold rush into the area began. This initial rush to stake mining claims soon gave way to mining companies that moved into the area, purchased claims and developed the mines on a large scale. A 12 mile wood pipeline pumped over 100,000 gallons of water from the Colorado River per day, and the railroad carried mine timbers from northern Arizona for use in the expansive underground workings. Ultimately, over 200,000 ounces of gold was taken from the mines in the area. Tumco was a typical mining town of its day. Historical accounts talk of rich eastern investors, unscrupulous charlatans and colorful characters in the raucous townsite and the mining boom ultimately leading to financial ruin. Although little can be seen of Tumco, during the boom time of the 1890’s, it supported a population of at least 500 people and the 40 and 100 stamp mills of the mine produced $1,000 per day in gold.

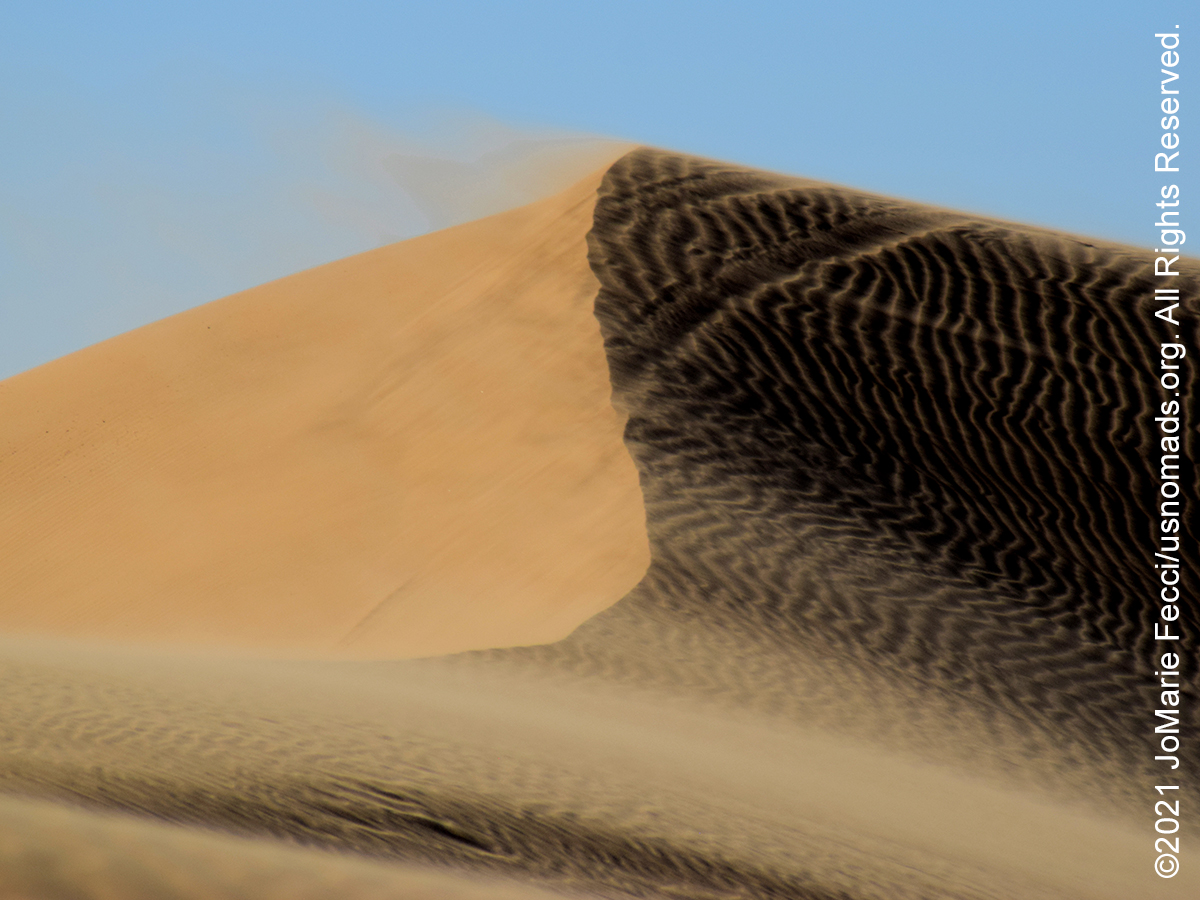

The Imperial Sand Dunes Recreation Area, located in the southeast corner of California near the border with Arizona and the Mexican state of Baja California, is the largest mass of sand dunes in the state. Formed by windblown sands of ancient Lake Cahuilla, the dune system extends for more than 40 miles in a band averaging 5 miles wide. Widely known as “Glamis” it is an off-road paradise, with an extensive open area for OHV use. The recreation area is part of the Algodones Dunes field which extends along a northwest-southeast line that correlates to the prevailing northerly and westerly wind directions. The name “Algodones Dunes” refers to the entire geographic feature, while the administrative designation for that portion managed by the Bureau of Land Management is the Imperial Sand Dunes Recreation Area. The dunes are now separated at the southern end by agricultural land from the much more extensive Gran Desierto de Altar, to which they once were linked as an extreme peripheral “finger”. The only significant human-made structures in the area are the All-American Canal that cuts across the southern portion from east to west and the Coachella Canal on the western edge. Most of the dunes located north of State Route 78 are off-limits to vehicular traffic due to designation as the North Algodones Dunes Wilderness, while the area south of this road remains open for off-highway vehicle use.